A year ago this week, Amazon shook up the audio world with its announcement of Amazon Music HD, a streaming service that today offers 60 million tracks in lossless 16-bit/44.1kHz CD resolution, plus “millions” of hi-rez tracks in resolutions up to 24/192. While lossless and hi-rez files were already available from Qobuz and Tidal, the leading streaming services all used lossy codecs, so Amazon’s embrace of hi-rez audio was big news.

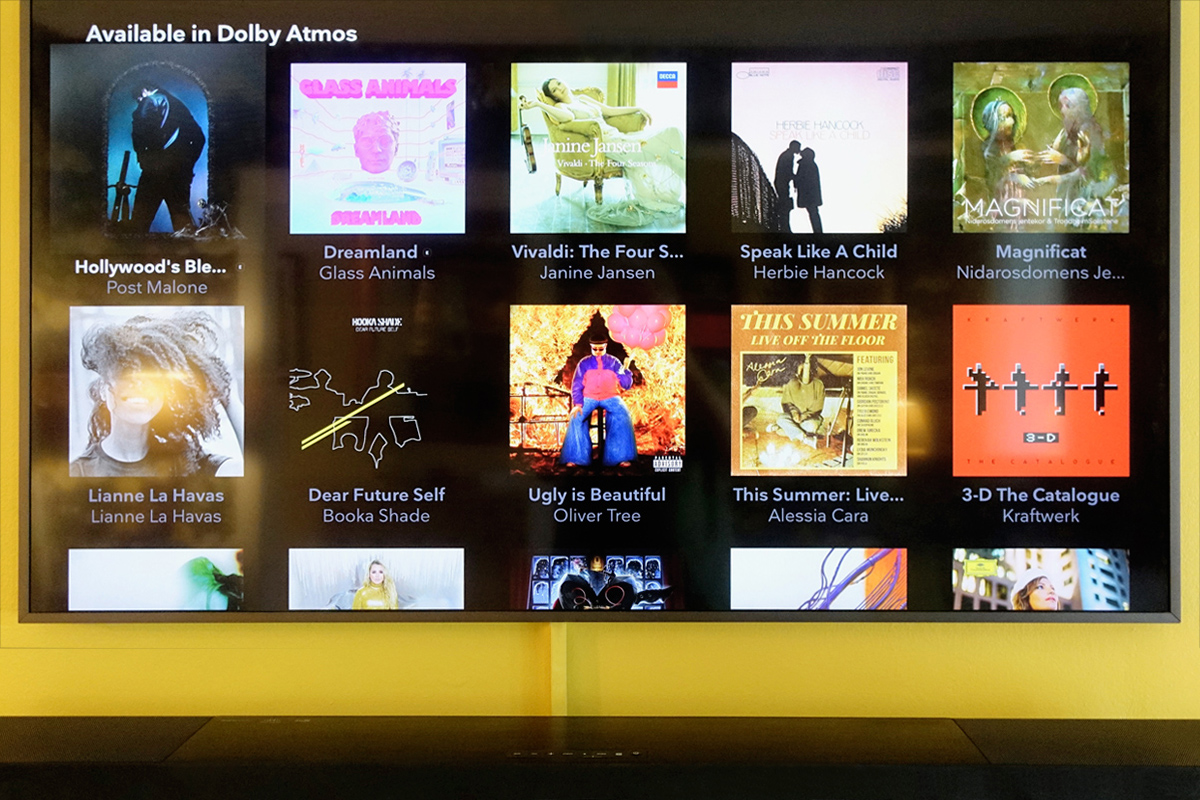

So it’s not surprising that another major announcement from Amazon slipped under my radar. A week after the launch of Amazon Music HD, Amazon and Dolby Laboratories announced that Amazon Music HD subscribers could thenceforth listen to a selection of Dolby Atmos-encoded music through Amazon’s Echo Studio smart speaker in surround sound.

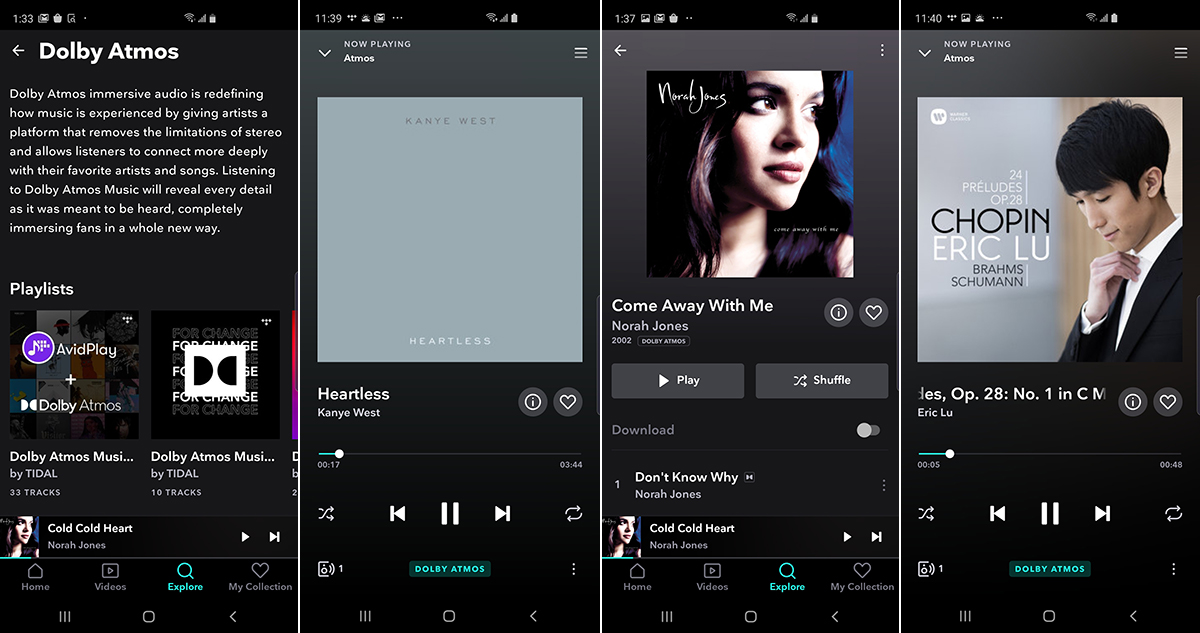

The prospect of listening to music through a tabletop speaker like the Echo Studio will thrill few audiophiles, but Dolby wasn’t done yet. In mid-December, they announced the availability of Atmos-encoded surround music via Tidal. Now Tidal subscribers can listen to Atmos-encoded music through headphones, Atmos-enabled soundbars and TVs, and full Atmos surround systems.

You can listen to Atmos Music from Tidal using an Atmos-capable Apple TV 4K, Amazon Fire TV, or Android TV media adapter connected to an Atmos-capable audio system -- e.g., an Atmos soundbar, or an Atmos A/V receiver and a full set of surround speakers. You can also use an Atmos-capable Android TV. For headphone listening, you’ll need an Atmos-capable smartphone or tablet.

The nth time around

This all sounds very interesting -- but haven’t we been here before? For almost half a century now, the audio and music industries have been trying to convince listeners that two channels aren’t enough to do justice to the music they love. First came quadraphonic sound, in the early 1970s. Beginning in the 1980s, home cinéastes used their surround-sound systems for music as well as movies. And in the 2000s, we had two optical music formats with surround capability: DVD-Audio (which disappeared after a few years) and SACD (which lingers as a niche format).

Some of these experiments bombed, and others fizzled. While live concerts on Blu-ray were a thing for a while, the fact is that for the vast majority of music lovers, two channels are enough, whether they listen through headphones or speakers. Music-only surround recordings and listening have never been more than a niche, and today that niche is very small.

When I asked the media-relations team at Dolby Labs what’s different this time, they responded with this:

The challenge that surround sound music faced was that it wasn’t easily accessible to consumers -- you needed high-end AV equipment and the tracks were available only on physical discs. This home-theater-style configuration limited listening to mostly home-entertainment-room environments. That’s not the case with Dolby Atmos Music.

Today, there are millions of devices in market that support Dolby Atmos. These range from living-room devices -- such as discrete home-theater systems, soundbars, and even TVs -- to more portable form factors such as smart speakers, smartphones, tablets, and PCs. Consumers can also experience Dolby Atmos Music via streaming services in addition to physical discs like Blu-ray.

I think this response is mostly spot on. For full-blown surround sound, you need a dedicated media room. It’s not practical for real-world, multipurpose living spaces. The multitude of speakers, other components, and cables required for true surround sound pose real domestic challenges.

While Atmos-enabled soundbars, TVs, and smart speakers can deliver spatial experiences that you can’t get from a stereo pair of speakers, they can’t match a good two-channel system in timbral accuracy, dynamics, maximum output, and freedom from distortion. And you can install a really good stereo in a multipurpose living area without disrupting domestic harmony. If it’s a choice between great stereo and compromised surround, which do you pick? For most audiophiles, the answer is easy.

Domestic harmony

I can see that dilemma easing. This year, I’ve reviewed two speakers that use Wireless Sound & Audio (WiSA) technology: System Audio’s Legend 5 Silverback active speakers ($2899/pair, all prices USD) and Klipsch’s RW-51M wireless powered speakers ($799/pair). Coming October 15 is a review of Buchardt Audio’s WiSA-capable A500 active speakers.

You can use WiSA speakers for two-channel stereo, as I did in my System Audio and Klipsch reviews (and as I’ll do when I review the Buchardts). But WiSA supports multichannel sound, including Atmos. That could make it possible to deploy a full Atmos system without running wires from the speakers to an AVR or processor. You could also expand your system in stages, starting with a stereo system built around a pair of WiSA-capable speakers, then adding surround, center-channel, and height-effects speakers, and a subwoofer. Sound would be sent wirelessly to all speakers -- the only wires would be the speakers’ AC power cords.

We’re not there yet. While there are WiSA-capable minimonitor, floorstanding, and center-channel speakers and subwoofers on the market, I know of no WiSA-capable height speakers -- as far as I’m aware, all height-effects speakers currently available are passive. There are also passive floorstanders with built-in height modules, each of which requires two pairs of cables back to the AVR: one for the main speaker, one for the height module. It would be great to have a wireless powered or active version of such a speaker, but I know of none. I gotta hope that some manufacturer somewhere is planning one.

In short, installing a full-blown Atmos immersive system in a multipurpose living area still involves big domestic hurdles. But I think we’re going to see more surround systems that distribute audio wirelessly to active speakers deployed throughout a room, some using WiSA, others based on proprietary technology. This will make it more feasible to have immersive audio in multi-use living areas.

Their responses to more of my questions made it clear that Dolby believes Atmos Music can deliver meaningful benefits to people who can’t or don’t want to install a full surround system:

The bigger barrier is that not every consumer will want to install this type of playback environment in their home. For example, people may not have a lot of space so they choose to purchase a sound bar or just use the built-in audio system within their TV. In parallel, more and more people are using smart speakers and mobile devices as their primary listening device.

We think the bigger opportunity for gaining more traction is to make Dolby Atmos experiences more accessible and available on all the devices consumers use to enjoy entertainment. We also feel it is equally important to make sure that these devices are not just available in different form factors, but at various price points.

Whether the user is listening to Dolby Atmos on a $200 smart speaker or high-end theater system, they are going to be able to enjoy the best possible experience that their device is capable of delivering.

Listening out loud

And the fact is, some of those “compromised” products deliver outstanding sound. A great example is Sennheiser’s Ambeo Soundbar ($2499.95). Using virtualization technology developed at Germany’s Fraunhofer Institute, the Ambeo delivers 5.1.4 immersive audio from Atmos content. I reviewed the Ambeo earlier this year, and think it’s now the best soundbar on the planet.

As there was no way I could deploy a full Atmos speaker array in the small living room of my Edwardian rowhouse, I asked Sennheiser if I could reborrow the review sample of the Ambeo. I connected my Apple TV 4K media adapter to one of the Ambeo’s HDMI inputs, and its HDMI output to the One Connect set-top box for my Samsung UN55LS003 55” Frame TV. Then I downloaded the Tidal app to the Apple TV and logged in to my Tidal account.

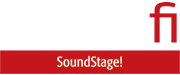

The Explore menu of the Tidal app includes a Dolby Atmos option with which you can find Atmos-encoded tracks and albums. In the Now Available section I chose View All and saw a total of 50 albums, including J Balvin’s Colores, Coldplay’s Everyday Life, Alanis Morissette’s Jagged Little Pill, R.E.M.’s Automatic for the People, and the Weeknd’s After Hours. There was also an interesting range of classical music, including a conductorless chamber version of Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons with violin soloist Janine Jansen, and conductor Daniel Barenboim’s cycle of Beethoven symphonies with the Staatskapelle Berlin.

My first thought: Is that all there is? I asked Dolby Labs about the number of music titles available in Atmos and how quickly the catalog is growing. “We don’t share this information publicly,” they said, “but we can confirm that the catalog is much more robust than what you are seeing.”

Indeed it is, as I confirmed when I began to explore Tidal’s Atmos playlists. Tidal has Atmos playlists devoted to the Band, Daniel Barenboim, Pat Benatar, Blondie, Glen Campbell, Johnny Cash, Bing Crosby, Lady Gaga and Bradley Cooper, Selena Gomez, Ariane Grande, Huey Lewis and the News, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Shawn Mendes, Yellowcard, and many others. There are also Atmos playlists devoted to genres, including country, jazz, pop, and hip-hop.

But just as it does with MQA-encoded Masters albums, Tidal doesn’t make it easy to find all the Atmos content it has available. There are lots of things I don’t like about Tidal’s interface, and this is one of them.

I spent several interesting hours listening to Tidal’s Atmos offerings through the Ambeo Soundbar, and comparing them with CD-rez and MQA versions played through my two-channel setup, an NAD Classic C 658 streaming DAC-preamp ($1649) and Elac Navis ARF-51 active speakers ($4599.96/pair).

I loved the Atmos mix of “Heartless,” from Kanye West’s 808s & Heartbreak (Roc-a-Fella). Kanye’s Auto-Tuned singing and natural rapping voices were at the center, the calliope and piano extending way out to the sides, the droning bass wrapping around everything. His shouts of “Hey!” in the second verse extended even farther out, which added to its impact.

Played through the C 658 and the Navis floorstanders, the CD-rez stereo mix sounded more closed-in, and the “Hey!”s had less punch. But predictably, the Elacs delivered more robust bass, more effortless dynamics, and more natural-sounding voices -- through the Ambeo, voices had a slightly edgy quality. Overall, I preferred the Atmos mix through the Ambeo -- that big sound just grabbed me.

With the Atmos version of “Cold, Cold Heart,” from Norah Jones’s Come Away with Me (Blue Note), the Ambeo created a huge soundstage extending far to the sides and out into the room. Jones’s voice was right at the center, with her piano slightly elevated and wrapped around her voice, Adam Levy’s muted electric-guitar chords way off to the left, and Lee Alexander’s double bass way off to the right.

When I played the 24/96 MQA version of the stereo mix through the C 658 and ARF-51s, Alexander’s bass had way more snap and depth, Levy’s guitar chords more body, and Jones’s piano more sparkle. I also heard more nuances in her singing through the Elacs, and her voice sounded more natural -- through the Ambeo it was more papery. Again, all this was to be expected. The MQA stereo mix sounded fantastic, but I missed the expansiveness of the Atmos version.

I was bowled over by the huge sound of the Atmos mix of a recording of Chopin Préludes by Eric Lu (Warner Classics) played through the Apple TV 4K and Ambeo Soundbar, and by the convincing piano tone and powerful dynamics. Predictably, piano tone was warmer and fuller from the 24/48 MQA version of the stereo mix through the Elacs. The stereo mix through the Elacs was very spacious, but not as much as the Atmos mix through the Ambeo, which delivered more of a concert-hall experience. Still, with this recording I preferred the Elacs for their greater tonal accuracy and superior articulation of Lu’s playing. But this says more about the capabilities of the Elac floorstanders and the Ambeo Soundbar than it does about the merits of the Atmos and stereo mixes.

Listening through headphones

For headphone listening, I used a Samsung Galaxy S10+ smartphone; it supports Dolby Atmos, and its 3.5mm stereo analog output allowed me to connect my HiFiMan Edition X V2 planar-magnetic headphones. The S10+ had no problem producing satisfying levels through the HiFiMans, thanks to their low-impedance, high-sensitivity design. One challenge was that the Atmos mixes were mastered at a higher level than the stereo mixes, which meant I had to adjust the volume every time I switched tracks.

I had high hopes for Dolby Atmos Music through headphones, based on a December 2016 visit to the Scarborough, Ontario, campus of Bell Media Inc., which operates some of Canada’s largest TV networks. Michael Nunan is senior manager of broadcast operations, audio, for Bell Media, and as a side project had recently mastered in Atmos an album by the Toronto world-jazz group Manteca. In his mixing studio, Nunan played me a track from the Atmos mix through a 7.2.5-channel system. As I wrote in an article for the Canadian magazine WiFi HiFi, “The instruments emerged from a 360° soundfield, completely divorced from the speakers. The horns were off to the right, drums played antiphonally behind me, and the keyboard played up front.”

A few days before my visit, Nunan had received a software renderer for making binaural mixes of Atmos content. Intended solely for headphone listening, conventional binaural recordings are made using two microphones, one inserted in each ear canal of a dummy head -- the idea being that the listener hears what the dummy would have heard had it been a human being. I remember hearing, many years ago, a binaural recording of pipe-organ music while visiting the exhibit of manufacturer Stax Headphones at a Consumer Electronics Show. It was mindblowing -- I perceived the sound as being entirely outside my head, as if I were in the sanctuary of a big cathedral.

Nunan then played a binaural rendering of a track from the Manteca album through Sennheiser HD 800 headphones and a Sennheiser HDVD 800 headphone amplifier. “The effect was just as impressive [as the 7.2.5 demo],” I wrote, “with an immersive soundfield that was completely outside my head. Nunan then switched back and forth between ’phones and speakers. The HD 800s are open-back headphones, and I found myself having to check whether I was listening to ’phones or speakers.”

The Tidal tracks I listened to through the Galaxy smartphone and HiFiMan planars didn’t match those lofty expectations, but they were still impressive.

With the Atmos mix of Kanye West’s “Heartless,” his Auto-Tuned singing and natural rapping voices were in the center of my head, the droning bass farther out to both sides, the artificial calliope even farther out, and the shouted “Hey!”s way off to both sides. The stereo mix was more closed-in, the sound more inside my head. Elements such as the calliope and echo effects stood out more clearly in the Atmos mix, and the “Hey!”s had more impact. But the Atmos version had a bit of a hard edge that I didn’t hear in the stereo mix. Overall, I preferred the Atmos version for its larger sound and greater impact, but not by a huge margin.

The Atmos mix of “Cold, Cold Heart” put Norah Jones’s voice at the center and her piano a little to the right, both inside my head. But Adam Levy’s muted guitar chords were well leftward, definitely outside my head, and Alexander Lee’s double bass was off to the right. All of these elements were beautifully differentiated from each other. The MQA stereo mix was much more closed-in, with everything inside my head. I strongly preferred the Atmos mix of this track.

The Atmos mix of the Chopin recording spread Eric Lu’s piano between my two ears. Rather than the concert-hall experience I’d had with this recording through the Ambeo Soundbar, through headphones it was if I were sitting next to Lu on his Steinway’s bench. While the MQA stereo mix was less expansive, Lu’s piano sounded more natural than in the Atmos mix: There was less reverb, which let me more clearly hear Lu’s interpretive gestures and thus better appreciate them. Here, I preferred the stereo mix.

Learning curve

I listened to many other tracks in Atmos, including a Beethoven symphony, a Vivaldi concerto, jazz numbers by Freddie Hubbard and Wayne Shorter, and songs by J Balvin, the Band, R.E.M., and the Weeknd. In most cases, I preferred the Atmos to the stereo mix.

My colleague Diego Estan had a very different response. After reading a draft of this article, Diego compared Atmos and two-channel MQA versions of several tracks, including “Cold, Cold Heart,” using Sennheiser HD 800 headphones connected to his Samsung Galaxy S10 smartphone. This was his response:

I preferred the two-channel MQA track every time. Atmos vocals sounded more distant, and a bit echoey to me. For me, that’s a deal breaker. I like vocal presence and intimacy. . . . In my opinion, good two-channel headphone listening can be very satisfying. It’s only worth applying fancy processing if the result is true out-of-the-head, speaker-like soundstaging. What I heard on Tidal with Atmos tracks is not that at all.

Certainly with headphones, I never had that out-of-head experience I got during that demo at Bell Media. Dolby said my experience might be a result of creative decisions by the artists and mix engineers:

In general, there are a lot of things that influence any sound experience. Atmos is not unique here. One factor is artistic intent -- for example, during the mixing process, the engineer is able to use binaural metadata to control how much space is given to an individual element. Often mixers will place vocals and percussive elements in “near” mode to keep the impact and intimacy that listeners expect from a headphone experience while putting effects such as synths, pads, background vocals in mid or far mode to allow for that more expansive space you mentioned. The engineers are able to monitor in binaural[,] so what you heard on Tidal was representative of what the creative team intended and wanted you to hear for those songs.

There are probably other factors at play. Unlike the binaural rendering I heard at Bell Media, the mixes I listened to via Tidal may not have been optimized for headphones. As Dolby’s media-relations team explained to me, when mixing for Atmos, the engineer creates “a single mix that is optimized for speakers and headphones. If the engineer wants to create a headphone version, all they do is add binaural metadata to the mix.”

On its YouTube channel, Dolby has posted interviews with several recording engineers discussing their experience with Atmos. In one video, Bruce Botnick, who has made Atmos mixes of music by the Doors and Mumford & Sons, said that, rather than doing a single encode as Dolby recommends, it’s often preferable to prepare two separate renderings: a binaural version for headphone listening, and a surround mix.

Steve Genewick

Steve Genewick

But many recording engineers believe there’s value in moving beyond two channels. Steve Genewick, a recording engineer at Capitol Studios in Hollywood, has created Atmos mixes of music by Aerosmith, Miles Davis, Norah Jones, Public Enemy, R.E.M., and many other artists. Here’s what he said in one of Dolby’s videos:

[With Atmos], there’s so much more space, and so much more to deal with -- in a good way. As mixers, we’ve always been jamming stuff into stereo, and carving stuff out to make it fit, and now we don’t have to do that. The palette is so much bigger. If two things are clashing, I just move them apart. I don’t have to EQ and compress stuff. I can keep the integrity of the music. We’re allowed to have dynamics. There’s a whole new set of tools, and a whole new set of space to convey the emotion of the song.

It’s still early days for Dolby Atmos Music. The tools for mastering in Atmos are evolving rapidly, and artists, producers, and engineers are still figuring out how to use them and best exploit their creative potential.

But the technology has a lot of momentum. Dolby Labs told me that the catalog of Atmos Music titles is growing quickly, and now includes new titles as well as Atmos versions of older albums:

For catalog tracks, these aren’t remasters, but rather reimagined versions of the original song or album that have been completely remixed in Dolby Atmos -- often with the original creative team’s involvement. With time we expect to see more new releases released in Dolby Atmos. Recent examples of day-and-date releases in Dolby Atmos include the latest albums from Coldplay, Halsey, Pearl Jam, The Weeknd, J Balvin, Alanis Morissette, Glass Animals, and others.

Those are big names; but even so, the vast majority of music is available only in two-channel -- and that’s not going to change anytime soon. But the ability to stream in immersive audio is big news. It might still be too early to state that at last the time has come for music in surround sound -- but it’s sure not dead.

. . . Gordon Brockhouse