It wasn’t exactly a coming-out party, at least not the one I expected. In a January 1 feature on Simplifi, Mike Jbara, vice-president and general manager of Lenbrook Media Group (LMG), said High End 2025 would mark “the coming-out party” for a new streaming service specializing in MQA-encoded music.

As we’ve previously reported on this site (as have almost all audio-enthusiast media outlets), Canada’s Lenbrook Industries purchased the assets of MQA Limited in September 2023 after the UK company had been put into administration, a form of bankruptcy protection. In early 2024, Lenbrook formed a new division, Lenbrook Media Group, to house MQA Labs as well as BluOS, Lenbrook’s multiroom music-management platform, and hired Jbara, formerly MQA’s CEO, to head the group. LMG announced plans for the streaming service in June 2024.

I interviewed Jbara last December to find out more about Lenbrook’s plans for MQA and to get the lowdown on the service. Jbara told me that the service would receive a soft launch early in 2025, followed by a “coming-out party” in Munich in May.

Hurry up and wait

LMG did host an MQA event in Munich, but made no announcement about a commercial launch of the service. During High End, Lenbrook demonstrated several MQA technologies, including Qrono d2a digital-to-analog conversion, Foqus analog-to-digital conversion, the Endura digital-audio workstation (DAW) plugin, and Airia scalable audio encoding-decoding. They also gave visitors a sneak preview of how the service would be integrated into Lenbrook’s BluOS music-streaming platform.

I didn’t attend High End, so I arranged to meet with Jbara at Lenbrook’s headquarters in Pickering, Ontario. That meeting took place in late August. I’ll cut to the chase. To this point Lenbrook has made no official announcements about the service—nothing about the launch date, pricing, catalog, or regions. During our August meeting, Jbara told me that negotiations with labels about licensing content are ongoing. He also said that Lenbrook had already engaged a supplier for editorial content for the service, and that features like playlists would be human-curated.

In a recent email, Jbara confirmed that Lenbrook will shortly make the playback engine for the service available to software and hardware partners such as Roon, Audirvāna, Libre Wireless Technologies, Pixel Magic, StreamUnlimited, and of course BluOS, so that they can build it into their own streaming platforms. “We hope they all integrate it before the service goes live,” he stated, “but of course, that is up to them and their hardware partners and consumers. There are also hardware partners who manage their music integrations directly and we will support direct hardware integrations as well.” Jbara also confirmed that Lenbrook plans to implement an endpoint model similar to Spotify Connect, Qobuz Connect, and Tidal Connect, so that users can cue up music in the app for the service and then transfer playback to a supported component.

From our discussions, it became clear that Lenbrook’s MQA music service will not go live in 2025. Not only is there no official launch date, the service does not yet have an official name. That’s not to say that Jbara didn’t have lots to talk about in Munich, or during my visit to Lenbrook.

Throughout our August meeting, Jbara sat next to me, cuing up music and making system adjustments on his smartphone and laptop. The demo system comprised a Bluesound Node Icon streaming preamplifier, an NAD Masters M23 power amplifier, and a pair of PSB Synchrony T800 floorstanding loudspeakers. This was almost identical to the setup Lenbrook used in its demo room during High End. At Munich, Lenbrook also had workstations where people could listen to demos through headphones.

Foqus A-to-D

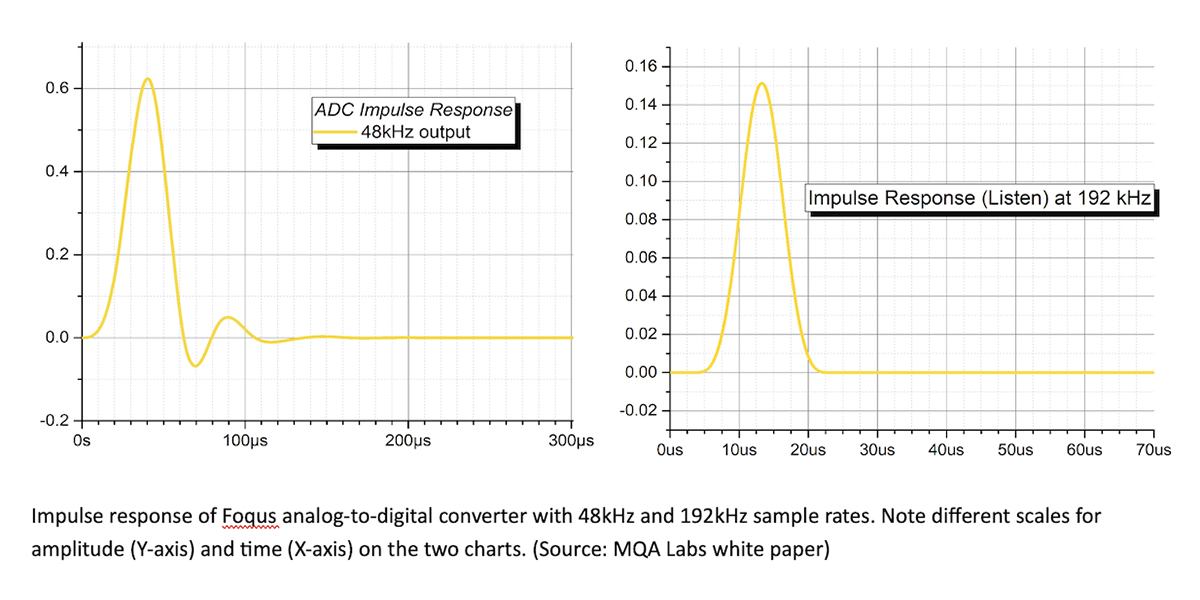

In a white paper on its Foqus analog-to-digital conversion technology, MQA Labs states that Foqus-enabled ADCs provide “a huge uplift in transparency by avoidance of quantisation time blur” compared to conventional sigma-delta ADCs. A Foqus-enabled ADC can produce 48kHz output with no pre-ringing and only minimal post-ringing and 192kHz output with zero pre-ringing and post-ringing, the white paper states.

Foqus is obviously relevant for sound recording, but it has consumer applications as well. Many components convert incoming analog signals to digital so that DSP-enabled functions such as room correction and EQ can be applied. Foqus must be implemented in hardware, at the chip level. On May 12, ESS Technology announced the first Foqus-enabled ADC, the ES9823MPRO. Two days later, NAD Electronics announced the Masters M33 V2 streaming integrated amplifier, which features Qrono D-to-A and Foqus A-to-D conversion.

At Munich and during our meeting in Pickering, Jbara demonstrated MQA’s Foqus technology using recordings by Chris Wright, an independent UK musician who specializes in folk, country, and bluegrass music. Wright also happens to be a senior engineer and developer with Lenbrook Media Group. Jbara played three tracks, all recorded at the same session using a workstation equipped with an ESS demonstration board that allows engineers to capture two channels of audio with Foqus and two channels without Foqus.

The first two selections were 24-bit/48kHz recordings of solo-guitar music: “Dear . . .,” a gentle ballad by Japanese guitarist Kotaro Oshio, and a fast finger-picked version of Chet Atkins’s “Freight Train” (Wright’s performance was based on Oshio’s cover of this country classic). With both tracks, Wright’s instrument sounded harmonically richer and fuller-bodied on the version with Foqus encoding. The upper strings carrying the melody had less glare. The differences were nowhere near night-and-day, but even though this was a sighted comparison, I’m confident in my belief that the version made with Foqus A-to-D sounded better.

The third selection was a 24/192 recording of Bob Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right,” with Wright singing and playing guitar. When Jbara switched to the Foqus version, I noticed richer overtones in Wright’s guitar and less digital glare. I hadn’t noticed the glare when Jbara played the straight 24/192 file, but I certainly noticed the absence of glare on the Foqus version.

Plugins

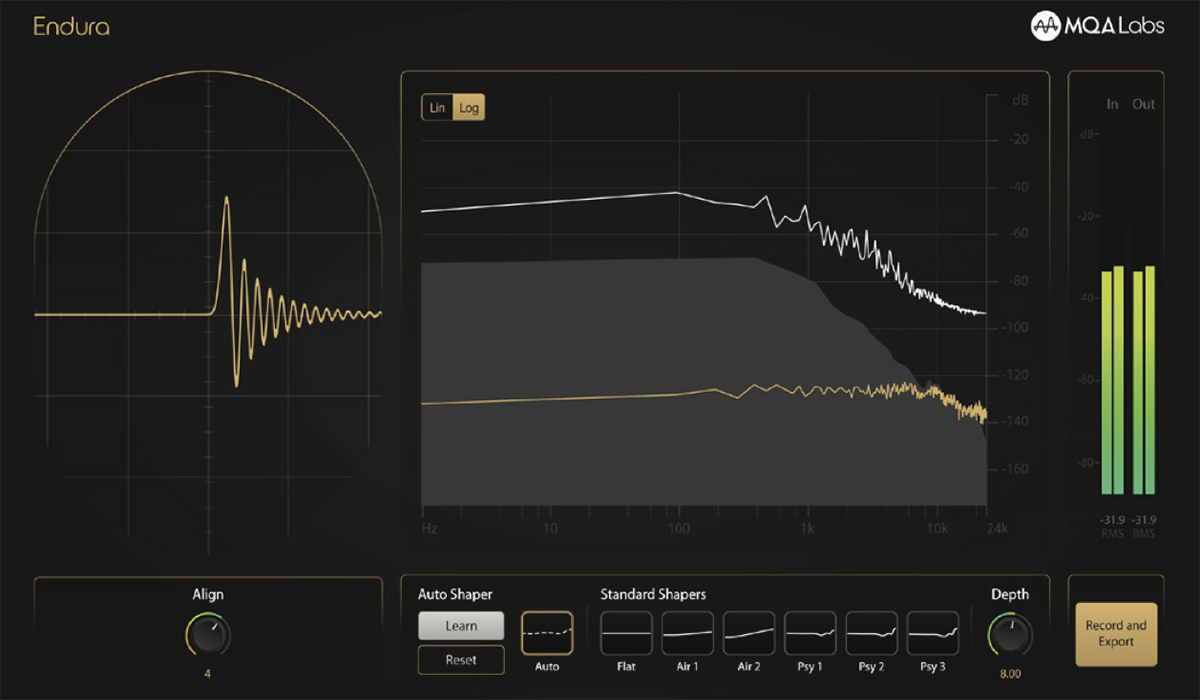

On the eve of High End, MQA Labs officially released two DAW plugins for audio capture, mixing, and mastering. Intended for recording, overdubs, and mixing, the input plugin, called Inspira, lets users adjust the impulse response of the A-to-D filter and add low-level noise (dither) that helps uncover fine detail. Applied as the last step on the DAW’s output bus after the master fader, and immediately before exporting the track as a WAV or FLAC file, the output plugin, called Endura, also allows noise-shaping and impulse-response adjustments.

As Jbara discussed in my January 1 feature, the plugins output standard PCM files. “The plugins create an interesting ecosystem because people will be essentially creating MQA-sounding PCM audio,” he explained. “That’s going to be on every service. You’ll be able to go into Amazon and get something that’s not called an MQA master, but has the benefit of somebody using MQA in the studio.”

For the second demonstration during our August sit-down, Jbara played two versions of two songs by the American alt-pop artist Ally Evenson from her 2025 album Blue Super Love. Evenson’s producer had provided Lenbrook with these 16/48 FLAC files, Jbara told me. One version of each song had been processed by the Endura plugin using the default settings.

On “Virtual Bottle,” the dense, reverb-laden mix was more open-sounding on the Endura version. There was more space around aural objects. The echo effects around Evenson’s voice were less harsh with the processed version. The electronic drum sounds that appear all over the soundstage were just as crisp on the Endura version, but less brash. The acoustic guitar sounded a little richer.

Similarly, on “Something in the Water,” there was less glare around Evenson’s voice in the version with Endura, and it was easier to hear into the dense mix. As with the Foqus demo, I found the differences between the two versions of both tracks clearly audible, but definitely not night-and-day.

Matt Bonaccio heard the same demo at Munich during High End 2025 and he had a different impression. “Simply put, it was a night-and-day difference,” Matt reported. “The music sounded great in the original version, as though it’d been competently recorded, but stepped up several degrees in immediacy, soundstage depth, and spatial information in the ‘corrected’ version. Sounds simply seemed to emerge from nowhere and had a more 3D feel to them.”

Airia

Jbara’s final technology demo during our get-together was Airia encoding-decoding. Airia dynamically adjusts data rate to deliver the best possible sound quality without rebuffering.

It can be used to send CD-resolution and hi-rez music over public data networks, as well as through Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and UWB (ultra-wideband) connections for local audio transmission, for example to send audio from an Airia-capable smart device to Airia-equipped headphones. It’s an encode-decode technology, so it must be supported by both the transmitting and receiving devices.

The streaming service that Lenbrook is developing is based on Airia. The service will accept MQA or PCM files from content providers, including PCM and MQA files captured through Foqus-enabled ADCs and PCM and MQA files processed with Inspira and/or Endura. But all these files will be converted to Airia files and these will be what the service streams.

For the demonstration of Airia in Pickering, Lenbrook had created a back door to their Wi-Fi network so that Jbara could adjust throughput. He started streaming a 24/48 lossless file of a Fleetwood Mac song with the network speed set at 3Mbps. At that point, the server was sending lossless audio to the Bluesound Node Icon. After a few minutes, he throttled network speed to 500kbps. To accommodate the reduced throughput, the server scaled data rate dynamically as it reloaded the playback cache, applying compression as necessary. The process was completely seamless. There were no dropouts or clicks signalling that something had changed, nor did I hear anything (e.g., a loss of transparency, constricted soundstage, vague imaging) that would betray the fact that the stream was now being compressed.

Next, Jbara boosted throughput back to 3Mbps, after which the server began sending lossless audio. Again, the change was completely seamless. According to Jbara, there are streaming platforms that will automatically scale back resolution and apply compression to adapt to deteriorating network conditions. But the ability to scale back up when network conditions improve is unique to Airia, he said.

What I missed

Something I regret not seeing in my August get-together with Jbara is the demo of the BluOS integration of the streaming service Lenbrook is planning.

Also, Jbara did not demonstrate MQA’s digital-to-analog conversion technology during our meeting. Qrono d2a is already featured on two Lenbrook products: the Bluesound Node Icon streaming preamplifier and the NAD Masters M33 V2 streaming integrated amp.

What about non-Lenbrook brands? In my January feature on Simplifi, Jbara said that “there are going to be a lot of new products” with Qrono d2a. I asked him about this during our August meet-up, and he listed audio brands based in the UK, Asia, and North America that plan to introduce products with MQA’s digital-to-analog technology. Subsequently, Hong Kong-based Lumin announced that it had implemented Qrono d2a on several of its streaming DACs.

Clearly, Lenbrook is up to a whole lot with MQA—even if that coming-out party wasn’t what some of us were expecting. It’ll be interesting to see what transpires in 2026.

. . . Gordon Brockhouse