When Linn Products announced its Series 3 active loudspeaker in October 2019, the Scottish company called it “the world’s best-sounding wireless speaker.” Given that bold claim, Linn chose an appropriate launch venue for the speaker. For several months, the Series 3 was available exclusively at Linn’s flagship showroom in Harrods department store in London, England. In 2020, Linn rolled out the Series 3 to its worldwide dealer network.

Linn says the Series 3 is its “first product with plug-and-play setup and doesn’t require specialist installation. You can take it home, plug it in, and start listening immediately.” The Series 3 has built-in Ethernet, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and HDMI ARC. It works with Linn’s Kazoo app, available for Android, and can be integrated into a Linn DSM whole-home music system.

The Series 3 also supports Apple AirPlay and Spotify Connect. Spotify subscribers can cue up music in the Spotify app on a mobile device or computer, and then transfer playback to the Series 3 via Spotify Connect. You can also stream to the Series 3 via AirPlay from any audio app on an Apple device, or from an iTunes library on a Windows PC.

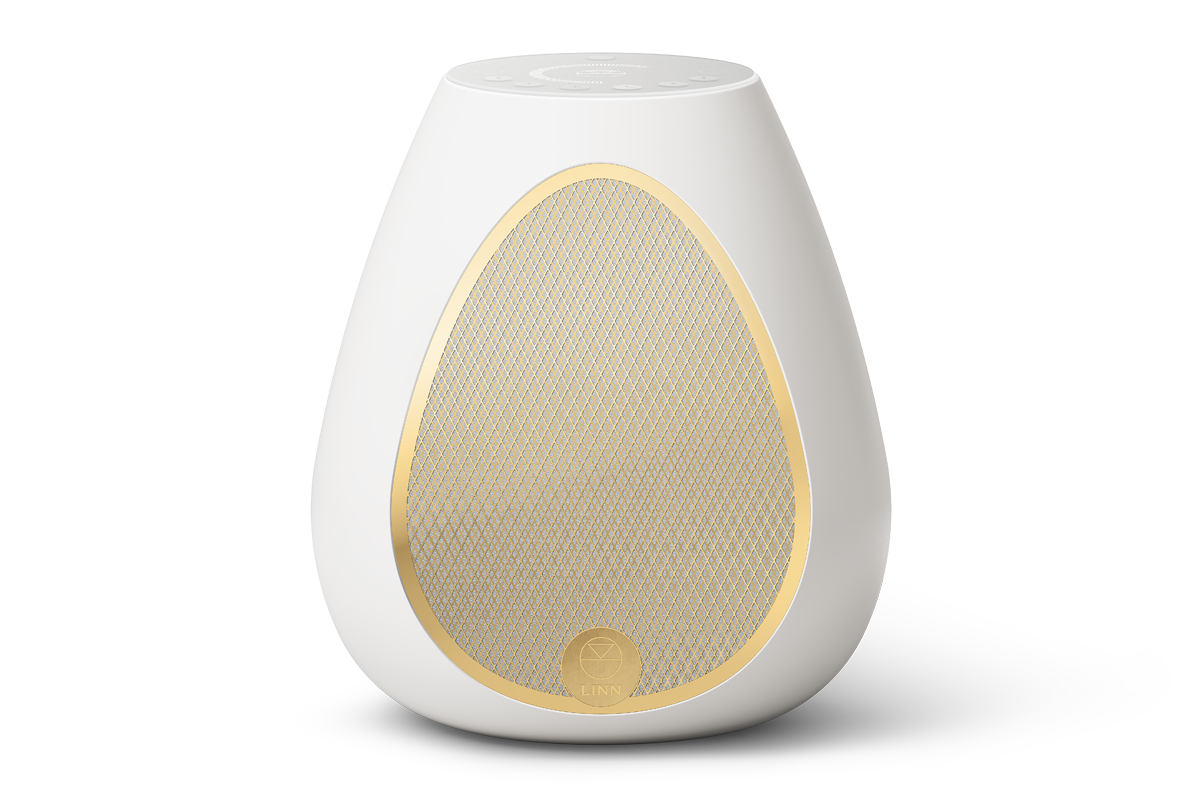

Is the System 3 “the world’s best-sounding wireless speaker”? I’ll get to that question, but it’s definitely among the most expensive. A single Series 3 speaker, intended for monaural playback, will set you back $4390 (all prices in USD); a stereo pair sells for $8105. Matching stands are available at $467 each.

The Series 3 is also one of the most unusual-looking wireless speakers I’ve seen. It has a unique teardrop shape, with a flattened top that slopes downward and forward. The molded enclosure has a soft Mineral White finish. On the front is an egg-shaped wire-mesh grille with a Linn badge at the bottom. Purchasers can choose between gold and chrome grilles.

Inside and out

Behind that striking exterior is some very slick technology. The Series 3 is a two-way sealed design, with a 6.3″ midrange-bass driver crossed over at 2.1kHz to a 0.75″ silk-dome tweeter. Each driver is powered by a 100W class-D amplifier. The tweeter is based on Scan-Speak’s Illuminator design, and the midrange-woofer is derived from SEAS’s Excel driver. Phil Budd, Linn’s head of acoustics, told me via email that both drivers have a few “proprietary tweaks,” like the woofer’s high-excursion motor system and Nextel-coated cone and dustcap. The Series 3’s specified frequency response is 42Hz–22kHz, ±3dB.

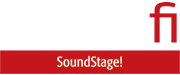

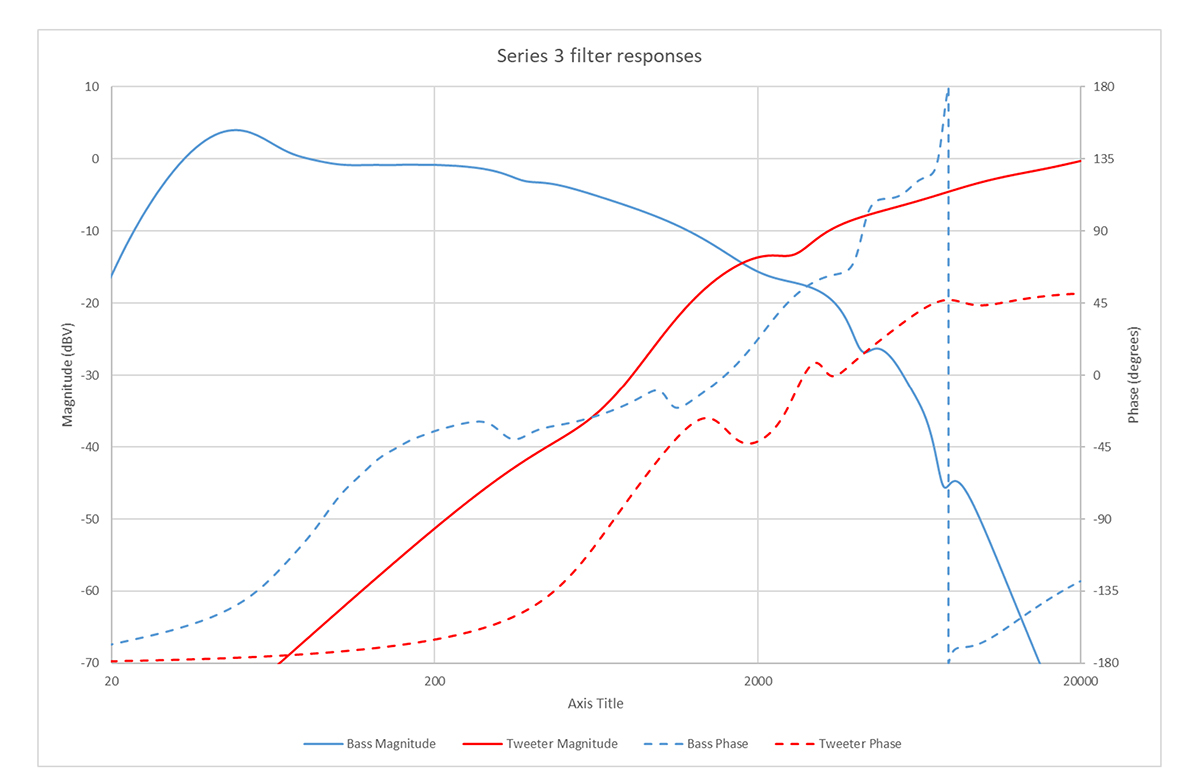

The Series 3’s secret sauce is its Exakt crossover, implemented in DSP. Crossover settings are adjusted at the factory, based on measurements of the drive units used in each individual loudspeaker. After purchase, Linn’s cloud-based Space Optimisation software can be used to tailor the Series 3’s response for your listening environment.

Budd explained that Linn’s Exakt technology aims to counteract the three sources of phase distortion—the drive units, the crossover, and the varying distances between each driver and the listener— in a traditional analog loudspeaker:

Exakt technology seeks to remove all three sources of phase (time) distortion in order to faithfully reproduce, in both frequency and time, the recorded signal.

To remove the phase distortion of the drive units, we effectively pre-correct the natural magnitude and phase response of each unit. We use a model-based approach supported by measurements of the drive units deployed into each individual loudspeaker we build. We model data which is used to correct both the magnitude and phase response of each driver to be near flat to at least two octaves above and below its expected operating bandwidth.

We then apply a linear-phase crossover (something that can only truly be done in a digital crossover) to the pre-corrected (linear phase) drive units.

Finally, during setup, using Space Optimisation, we establish the varying distances from each drive unit to the listening position and adjust the time delays for bass and tweeter signals to ensure the linear phase response of each drive unit arrives in synchrony.

It is worth noting that the model data which is used to pre-correct the drive units is bespoke to the speaker in front of you . . . . Each Series 3 loudspeaker actually has its own unique crossover filter tailored for the units in the cabinet.

“Why does all this matter?” Budd asked rhetorically:

Any variation in phase response of the system will manifest itself as a frequency-dependent time delay; each frequency will exhibit its own unique time delay. In conventional analogue loudspeakers (both passive and active), the highest frequencies experience little to no delay, with time delay increasing as frequency decreases. For a musical note this has significant consequences. A musical note has a fundamental tone and a whole host of harmonics, each of which relates to the fundamental in both magnitude and phase. The time-smearing effect of analogue loudspeakers results in the harmonics being reproduced before the fundamental—clearly not a good thing!

There are two versions of the Series 3. For monaural listening, say, in a kitchen or bedroom, all you need is a Series 3 (301). To configure a stereo pair, you add a Series 3 Partner (302). As noted in my introduction, you can buy the stereo pair as a package, or buy the Series 3 (301) on its own. Listeners who want to upgrade a Series 3 for stereo playback can purchase a Series 3 Partner separately for $3715.

Both speakers have the same dimensions and weight: 9.8″W × 11.7″H × 8.1″D, and 15.2 pounds. In a stereo pair, the Series 3 (301) acts as the primary speaker, as it houses the network streamer and the HDMI ARC input for connection to an HDTV.

On the back of the Series 3 (301) there are two Ethernet ports on the lower left side. The top one, labeled Ethernet, is used for hardwiring the speaker to a network router or access point. The bottom port, labeled Exakt Link, is used for connecting the Series 3 to another speaker. Typically, this will be a Series 3 Partner to enable stereo playback. Below the Ethernet ports is the HDMI ARC port; you can adjust the Series 3’s volume with a connected TV’s remote during video playback. On the right is an on/off rocker switch and a three-prong IEC power inlet.

At the top of the Series 3’s sloping top panel is a touch control for waking the speaker up from standby mode. On either side are touch controls for turning volume down and up; the volume setting is indicated by illuminated bars around the panel’s perimeter. Along the bottom are six touch controls for initiating playback from presets configured in the Kazoo app. These can be a hardwired input (just HDMI ARC on the Series 3) or internet radio stations. In the center is an illuminated Linn logo.

The only element on the Series 3 Partner’s top panel is an illuminated Linn logo. On the back panel are two Ethernet ports. The top one is labeled Exakt Link, and is used to connect the Series 3 Partner to the primary Series 3 (301). The speaker comes with a 3m Ethernet cable for that purpose. The bottom port is for daisychaining the speaker to other Linn components, such as a Linn Sondek LP12 turntable with internally mounted Urika II phono stage.

As noted, the Series 3 has built-in Bluetooth and Wi-Fi. Maximum resolution via Ethernet and Wi-Fi is 24-bit/192kHz PCM.

Setup and software

For my review, Linn provided a Series 3 with a chrome grille and a Series 3 Partner with a gold grille. I’ll be honest: my wife and I found the speakers a little strange-looking, but their styling grew on me. The Series 3’s industrial design is striking, but also polarizing.

I placed the speakers atop 28″ Monoprice Monolith speaker stands located on either side of the electric fireplace in our living room. The speakers were 6′ apart and 7′ from the sweet spot on the end cushion of the sectional sofa on the opposite wall. Their backs were 18″ from the wall behind them. The right speaker was 41″ from the right wall, and the left speaker was near a wide archway that opens into an adjoining room. I connected the primary speaker’s HDMI ARC port to the One Connect breakout box for my 55″ Samsung Frame TV.

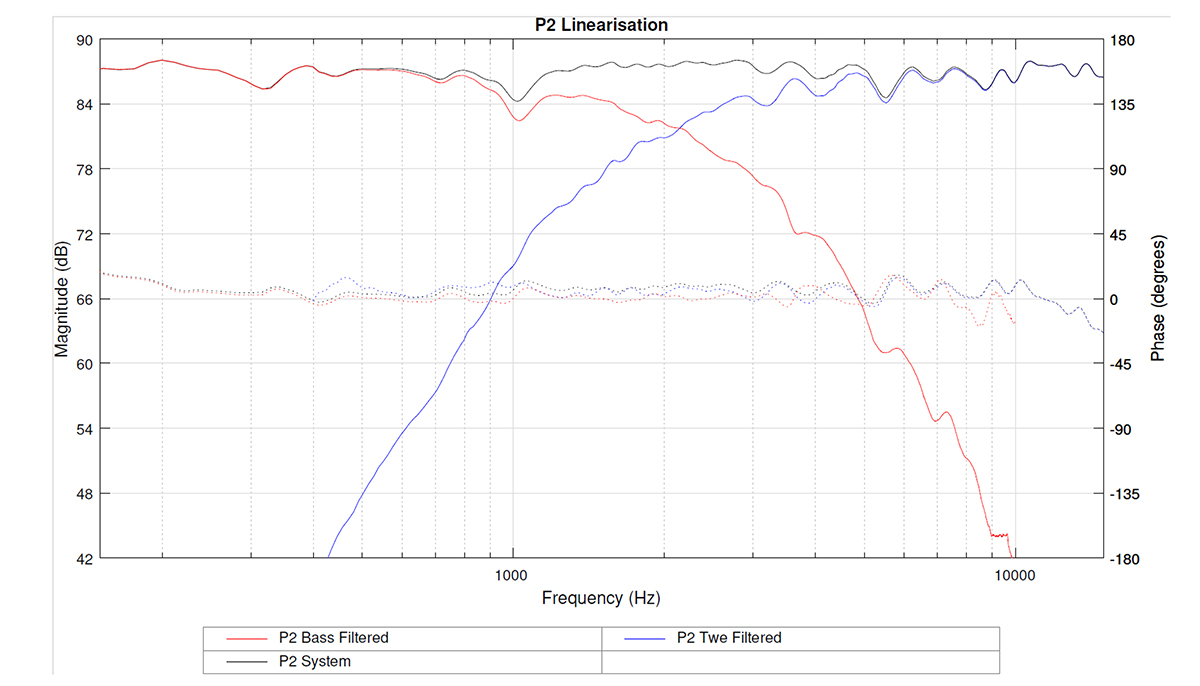

The Series 3 comes with a Quick Start Guide that’s one of the most rudimentary I’ve ever seen. The guide provides basic instructions for enabling Wi-Fi with a router that supports WPS pairing. My Google Wifi mesh network does not; per the guide, I pointed my browser at www.linn.co.uk/setup, where I found several videos on setting up and using the Series 3. One of these, entitled “Alternative Wi-Fi Setup,” is for users with routers that don’t support WPS.

Following instructions in the video, I opened the Wi-Fi Settings menu on my Google Pixel 4a smartphone and selected the Series 3 hotspot from the list of available networks. The list cautioned that internet access wasn’t available through that hotspot—I knew that. Next, per the video, I entered the URL of the setup web page in the address line of my phone’s browser, and was greeted with an error message: “This site can’t be reached.” Apparently, Android 12 automatically uses mobile data when internet access isn’t available over Wi-Fi, so the browser was looking for a web page on the internet when it should have been looking on the Series 3’s hotspot network. Switching off mobile data solved that problem; now entering that URL took me to the Series 3 setup page, which showed a list of available networks. After I selected my network and entered the password, the Series 3 connected to my home network.

Now I was able to stream music to the Series 3 speakers via Spotify Connect and AirPlay, and from the Roon Core on the Mac Mini in my second-floor home office. Roon gave me the option of streaming to the Series 3 via AirPlay or Linn streaming. I chose the latter option as it supports hi-rez playback up to 24/192; via AirPlay, Roon resamples everything to 16/44.1.

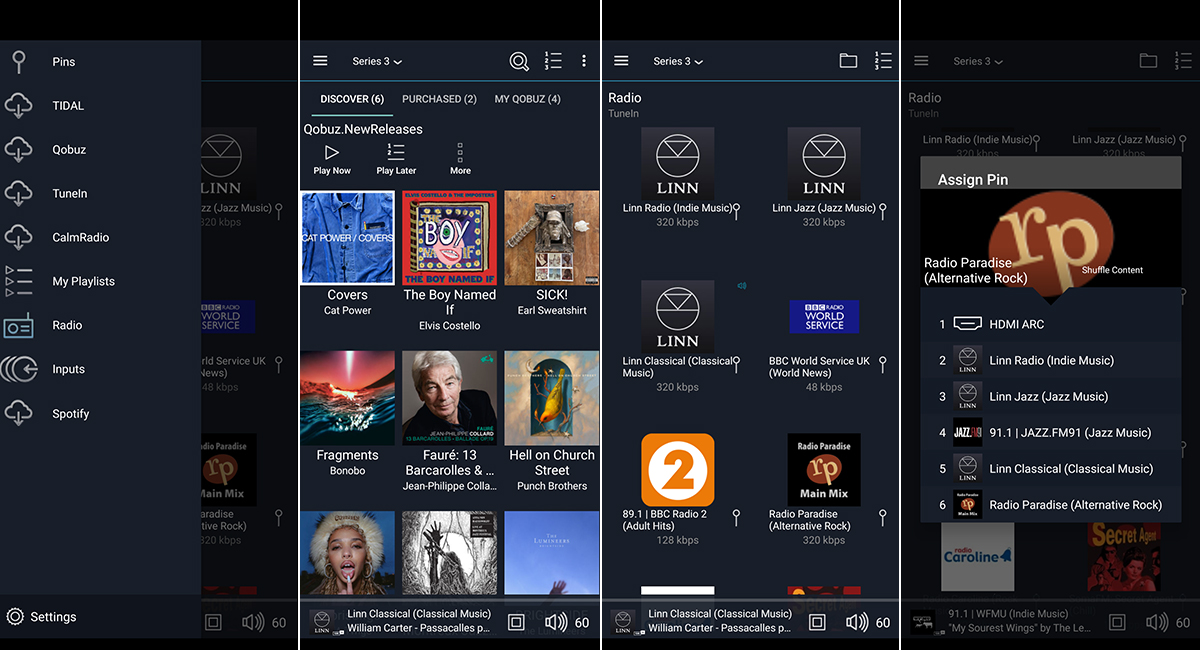

I could also play music from Linn’s Kazoo app, which has integrated support for Qobuz, Tidal, TuneIn, and Calm Radio, plus a list of internet radio stations curated by Linn. In that list, there’s a little pin logo beside each station; tapping it creates a “pin” for that station. You can access pinned stations directly from the Pins menu in the Kazoo app, or by tapping the corresponding preset control on the primary speaker’s top panel.

I ran into a few weirdnesses with the Kazoo app. If I was logged into TuneIn, I couldn’t initiate playback of a pinned station from Linn’s list—not in the Kazoo app and not from the preset controls on top of the primary speaker. And the only station that showed up in the Radio menu of the app was the TuneIn station I was playing. Another problem: if I went into the Settings menu, there was no way to exit back to the main menu. I had to close the app and start again.

While I found the Kazoo app confusing and poorly organized, the fact is that you may not need it much in day-to-day use, especially if you’re mainly streaming via Spotify Connect or AirPlay. You don’t even need the app to switch to the HDMI ARC input. That will probably happen automatically when you start playing a movie or TV show on a connected HDTV; but if not, you can select the HDMI ARC input from the System 3’s top panel; by default, that input is assigned to the first preset.

I ran into one other complication. By default, in a stereo pair, the primary System 3 speaker plays the left channel, and the secondary speaker (the Series 3 Partner) plays the right channel. This designation cannot be changed in the Kazoo app. That would be a deal-breaker for me, because the only practical location for the small table that holds my components, including the One Connect breakout box for my Samsung Frame TV, is the right-front corner of my living room.

Fortunately, channel designation can be flipped using Linn’s web-based Manage Systems software. Manage Systems is used for other configuration tasks as well: notably, Space Optimisation, which changes the DSP settings of Series 3 speakers to compensate for room acoustics and speaker placement.

To use Manage Systems, I had to set up a Linn Account by clicking My Linn at the bottom of any page on Linn’s website. Then, when I selected Manage Systems, the software found my review pair of Series 3 speakers and presented a page with options for configuring them. The General menu showed the two Series 3 speakers. Clicking the > link beside each speaker took me to a page where I could change the channel designation for that speaker.

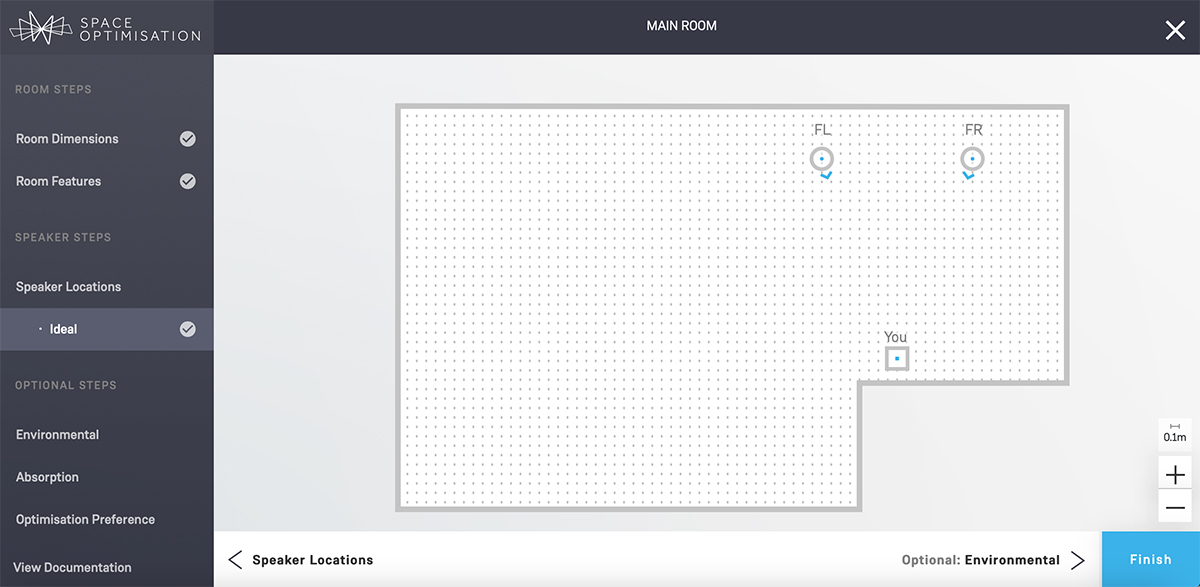

Clicking the Space tab in Manage Systems takes you to a menu where you can set up Space Optimisation. Essentially, this involves creating a layout of your listening room. If you’ve ever used an online tool like IKEA’s kitchen planner, the process will be familiar. Besides specifying room dimensions, you also provide structural information, such as the nature of each wall (concrete, drywall, or partition), and information on room features such as windows and doors. Next, you specify speaker location, height, and toe-in angle. When you’re finished, the software will optimize frequency and impulse response for your listening room. This calculation is performed on a server in the cloud, not your local computer, and takes several minutes. Once the calculation is complete, the software uploads new DSP settings to your speakers.

There are a few optional settings: Environmental, for specifying indoor temperature and humidity (useful in extreme climates); Absorption, for specifying the characteristics of room surfaces and features; and Optimisation Preferences, for specifying whether you want to prioritize flat frequency response or short decay time. Moving the slider control toward Shorter Decay Time will usually increase the amount of bass energy in the room. You can create profiles with different preferences, and switch between them in My Systems. This takes only a few seconds. I created two profiles, one with the default setting (80% flat frequency response, 20% short decay time) and one that would provide a bit more oomph (60/40).

After Gordon Inch, a product trainer for Linn, walked me through Manage Systems during a Zoom meeting, it took me about 40 minutes to model my room and transfer settings to my review samples. Doubtless, a Linn dealer who’s familiar with the software would get the job done more quickly.

Someone purchasing a Series 3 for monaural playback probably won’t bother with Space Optimisation, Inch told me, because the speaker will probably be used in different rooms around the house. “But if the speakers are permanently sited, say, beside a TV as I have them set up in my home, you should probably run Space Optimisation,” he added. “We would expect an optimization to be carried out by the dealer as part of the installation and to be included in the price of the product.”

But why make the dealer, or the user, go through this process, instead of offering an automatic system that uses test signals and measurements to model room behavior?

Microphone-based systems can be thrown off by ambient noise, Inch said, and are sensitive to mike placement. In my experience, neither of these are major issues. Microphone-based room-correction systems like Dirac Live provide step-by-step guidance on measurements. It’s a good idea to shut off noise sources like HVAC during calibration, but if a noise occurs, it’s easy to repeat a measurement. Certainly, I found Space Optimisation more complicated and time-consuming to use than Dirac Live. However, if optimization is being performed by the dealer during installation, this is probably a non-issue.

Inch cited one other reason for Linn’s approach. “We believe we get a better result from a 3D model than a microphone-based system.” Fair enough—Space Optimisation made a major improvement in the sound of the Series 3s in my living room.

Listening

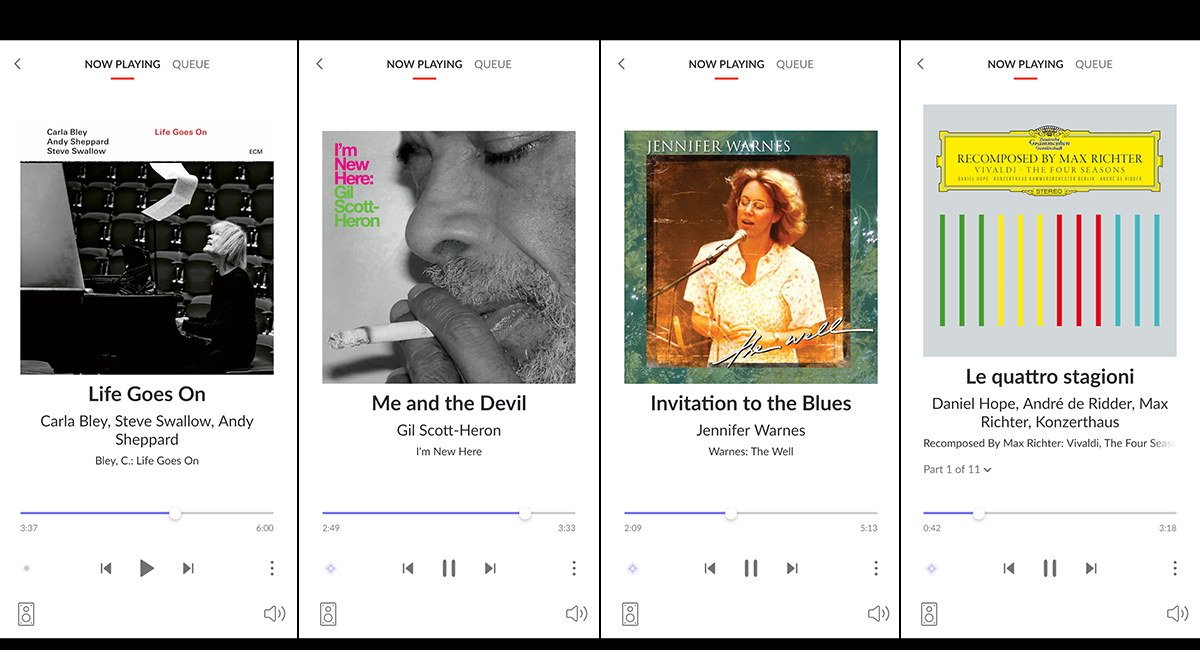

To determine how effectively Space Optimisation compensated for the serious standing waves in my living room, I cued up the titular suite of Life Goes On, by the Carla Bley Trio (24-bit/96kHz FLAC, ECM Records/Qobuz), in Roon. On this album, Bley’s husband, Steve Swallow, plays a five-string fretless electric bass guitar, whose lowest string is tuned to B0 (30.87Hz), about 10Hz lower than E1, the lowest note on a four-string bass.

With no optimization, the lowest notes of Swallow’s bass sounded a little faint, and also a bit muddy and indistinct. I attributed the faintness to the fact that the Series 3 speakers don’t go deep enough to fully reproduce the lowest notes of that five-string bass, and the muddiness to room modes in my listening environment.

I then switched to the default Space Optimisation setting—an 80/20 balance between flat response and decay time. The deepest notes of Swallow’s bass became a little fainter, but bass definition was much improved—that muddiness was gone. There were other benefits, as well. With optimization enabled, the aural images of Swallow’s bass guitar on the left, Bley’s piano in the center, and Andy Sheppard’s tenor saxophone on the right were more precise and more three-dimensional. Microdynamics were also improved, so I could hear the phrasing of the three musicians more clearly.

Next, I switched to the optimization setting I had created with a 60/40 balance between flat response and short decay time. Imaging and microdynamics were just as satisfying as they were with the 80/20 setting; but the tonal balance became a little warmer, and the deepest notes of Swallow’s bass sounded a little fuller—with hardly any increase in room-induced muddiness. This is the setting I used for the rest of my listening.

I loved the way this album sounded through the Linn speakers. Piano tone was uncolored and tonally consistent through the instrument’s entire range. Low-pitched chords and notes had the ideal degree of heft—remarkable for such small speakers. What impressed me most was the wonderful harmonic integrity of the Series 3s—that piano sounded so right. Dynamic shading was outstanding, making it easy to appreciate Bley’s wonderfully nuanced phrasing and pedaling. I’m tempted to say the way that Bley’s gentle attacks segued into the resonance of the piano’s soundbox was pure magic, but that doesn’t quite capture it. The transitions from attack, to sustain, to decay were completely, utterly natural.

The sound of Sheppard’s tenor sax was just as good. Again, the instrument sounded completely natural through its entire range, with a deeply satisfying sense of rightness. And again, dynamic shading was wonderful, so I could easily follow Sheppard’s varied breathing, blowing, and phrasing.

I’ve mentioned that the Series 3s seemed to run out of gas when Swallow was playing very low notes on his five-string bass. That’s true, but the fact is that those notes sounded pretty impressive, considering the compact form factor of the Linn speakers. And everything above those deep notes was ideal. I could hear the action of Swallow’s fingers on the strings. His rapid-fire runs were articulated beautifully.

Life Goes On is a playful, inventive album, and beautifully recorded as well. But it’s kinda mellow. How would the little Linns deal with something more intense? Very well indeed, as I confirmed by streaming Gil Scott-Heron’s cover of Robert Johnson’s “Me and the Devil,” from his extraordinary album I’m New Here (16/44.1 FLAC, XL Recordings/Qobuz).

After an ominous intro, with low, droning synth tones and quiet taps on a hip-hop drum machine on the right, the drama heats up, with nightmarish sounds appearing all over the soundstage: pounding hip-hop drumbeats in the rear left, manic handclaps in the center, zingy machine-gun synth phrases in the right center, subterranean synth notes on the far right, all enveloped in sampled strings across the rear. These sounds jumped out of the speakers without a hint of distress or compression. While the deepest drumbeats and synth notes were a bit fainter than I’d have liked, they were mighty impressive for such small speakers. Every sound was locked in place on the soundstage, creating a compelling sonic picture of an urban apocalypse. The star of the show was Scott-Heron’s raw, bluesy baritone. The Series 3 speakers captured his raspy wailing perfectly.

Through the Linns, Jennifer Warnes’s cover of Tom Waits’s “Invitation to the Blues,” from her 2001 album The Well (16/44.1 ALAC, BMG Rights Management), positively oozed atmosphere. The soundstage was huge and transparent, with every instrument occupying a clearly defined three-dimensional space: Doyle Bramhall II’s electric guitar on the far left, Armando Compeàn’s acoustic bass in the left center, Martin Davich’s piano across the front center, Lee Thornburg’s trumpet (sometimes played open, sometimes muted) on the far right, and Vinnie Colaiuta’s drum kit across the back. The speakers themselves disappeared; but the air between and behind them was alive with music.

As I had noticed with Carla Bley’s Life Goes On, there was a compelling rightness to the way the Linns rendered all these instruments—they all sounded harmonically complete. Compeàn’s bass sounded full, deep, and warm, with no bothersome bloat anywhere in its range—a tribute to the speakers themselves, and also to the way Space Optimisation had successfully dealt with the bass modes in my listening room. Colaiuta’s deft rim shots were fast, and his snare rolls wonderfully articulate; and his cymbals had an ideal metallic sheen with no splashiness at all.

Locked in the center right, Warnes’s voice sounded wonderful through the Linns: full and warm in the lower part of her range, tender and vulnerable in the upper part, uncolored throughout her whole range, and completely human. Consonants and sibilants were clear, but never hot or spitty, so that it was easy to visualize how Warnes was using her mouth, lips, and tongue to form the words.

Toward the end of the review period, Toronto got socked with over a foot of snow. Needing a break from winter, I cued up the four-part “Spring” concerto from Recomposed by Max Richter: Vivaldi—The Four Seasons (16/44.1 FLAC, Deutsche Grammophon/Qobuz). This version of the baroque classic by the Konzerthaus Kammerorchester Berlin, conducted by André de Ridder, features violinist Daniel Hope. In the lyrical passages in “Spring 2,” Hope’s solo violin had a wonderful silvery tone, and his playful skipping passages in “Spring 3” were beautifully articulated. I could sense the action of the rosined bow on the strings—not just during Hope’s solos, but in the orchestral strings as well. However, the sound was never scrapey or steely. The orchestral tone was beautifully transparent throughout; the cellos and double basses had a wonderful breathy quality.

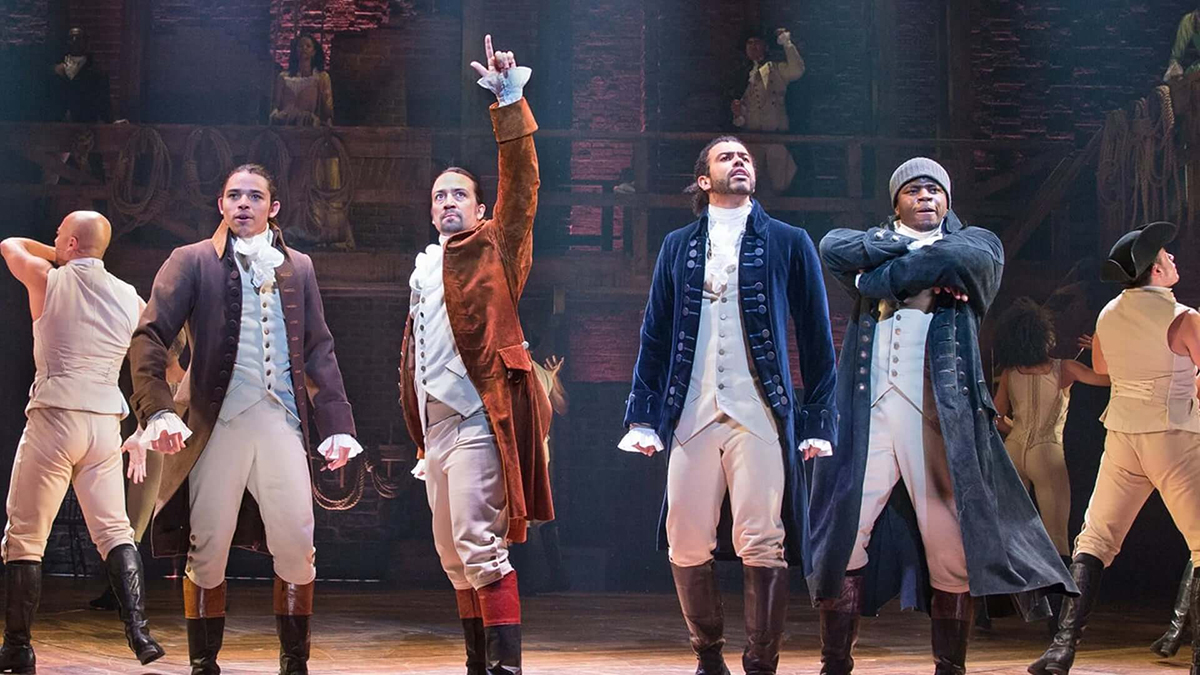

To hear how the Series 3 speakers would deal with a big theatrical production, I streamed the musical Hamilton from Disney+ to a Chromecast Ultra dongle connected to my Samsung Frame TV’s One Connect breakout box. The big number “My Shot” at the beginning of Act I sounded glorious through the Linn speakers. The rapping male voices—Lin-Manuel Miranda as Alexander Hamilton, Leslie Odom Jr. as Aaron Burr, Daveed Diggs as the Marquis de Lafayette, Anthony Ramos as John Laurens—sounded completely natural and perfectly intelligible. The big moments where the entire company sing “I am not throwing away my shot” and “Rise up!” were thrilling. The soundstage was huge—deep, wide, and high—matching the theatrical set on the screen of my TV.

Comparison

The closest comparison I had on hand was KEF’s LS50 Wireless II speakers ($2799.99/pair), a SoundStage! Network Product of the Year for 2021. While there’s a huge difference in price between the two speakers, they’re quite similar in terms of feature set. The LS50 Wireless II has a built-in network streamer that supports Apple AirPlay 2 and Spotify Connect. It’s a two-way active system, with a DSP-based crossover that optimizes both phase and amplitude response. One thing worth noting: the KEF Connect app is better organized and more functional than Linn’s Kazoo app. For one thing, the KEF makes it easy to flip the channel designations of the primary and secondary speakers.

Given the price differential, you’d expect the Linn Series 3 speakers to sound better than the KEF LS50 Wireless IIs; and they did. They were smoother, more inviting, and more transparent.

Through the KEFs, Gil Scott-Heron’s voice on “Me and the Devil,” had a bit of a hard edge that I didn’t hear with the Linns. Through the Linns, his voice sounded more coherent and more human. The nightmarish handclaps, synthesized drums, and high-pitched synth notes didn’t jump into the room as dramatically as they did with the Linns, yet they sounded harsher. The deep synth notes and bass drumbeats had a bit more texture through the KEFs, but sounded fuller and deeper through the Linns—and they hit quite a bit harder. The Linns created a deeper soundstage; with the KEFs, the sound was more confined to the plane between the speakers.

On “Invitation to the Blues,” Jennifer Warnes’s consonants and sibilants were a little hotter through the KEF speakers. Dynamic shifts were less natural—there seemed to be fewer gradations between loud and soft. Again, the soundstage wasn’t as deep as it was through the Linns. Armando Compeàn’s acoustic bass sounded leaner through the KEFs, fuller and warmer through the Linns.

On Max Richter’s reimagining of Antonio Vivaldi’s “Spring,” the tone of Daniel Hope’s violin didn’t quite have the lovely singing, silvery tone that I admired with the Linns—it was a little more truncated, and a tad steelier. The orchestral strings were also a bit wirier through the KEFs than they were through the Linns. And again, the soundstage was deeper with the Linns.

Conclusion

In this review, I’ve voiced a few concerns about Linn’s software. The Kazoo app is kinda flaky and Linn’s Manage Systems online tool is somewhat cumbersome. But none of this may matter if you’re a Spotify subscriber or Apple user and the dealer is setting up the speakers for you.

As to the sound of the Series 3s, I have no reservations at all. I loved every moment I spent listening to the little Linns. They were tonally accurate, coherent, and rhythmically adept. Their spatial presentation was superb. On recording after recording, the Series 3s created a soundstage that was wide, deep, and high, with near-holographic placement of instruments and voices.

So is the Series 3 “the world’s best-sounding wireless speaker?” Obviously, there are many wireless speakers that I’ve never heard, including some expensive, high-end models; so I can’t answer that question definitively. But this review sure left me wanting to hear other active Linn speakers in my home—maybe one of the company’s active floorstanders.

. . . Gordon Brockhouse

Associated Equipment

- Active loudspeakers: KEF LS50 Wireless II.

- Speaker stands: Monoprice Monolith (28″).

- Display: Samsung UN55LS003 UHD TV “The Frame.”

- Sources and control devices: Apple Mac Mini computer (mid-2011) running Roon Core 1.8, HP Spectre X360 notebook PC running Roon Control 1.8 and Audirvana 3.5.51, Apple iPhone 8 and Google Pixel 4a (5G) smartphones.

- Network: Google Wifi four-node mesh network.

Linn Series 3 Active Loudspeakers

Price: $8105 per pair. The Series 3 (301) can be purchased on its own for downmixed mono playback for $4390. The Series 3 Partner (302) can be purchased separately as an upgrade for $3715. Dedicated stands are available at $467 each.

Warranty: Five years, parts and labor.

Linn Products Limited

Glasgow Road

Waterfoot

Glasgow G76 0EQ

United Kingdom

Website: www.linn.co.uk